When surveillance meets incompetence

Last week brought an extraordinary demonstration of the dangers of operating a surveillance state — especially a shabby one, as China’s apparently is. An unsecured database exposed millions of records of Chinese Muslims being tracked via facial recognition — an ugly trifecta of prejudice, bureaucracy and incompetence.

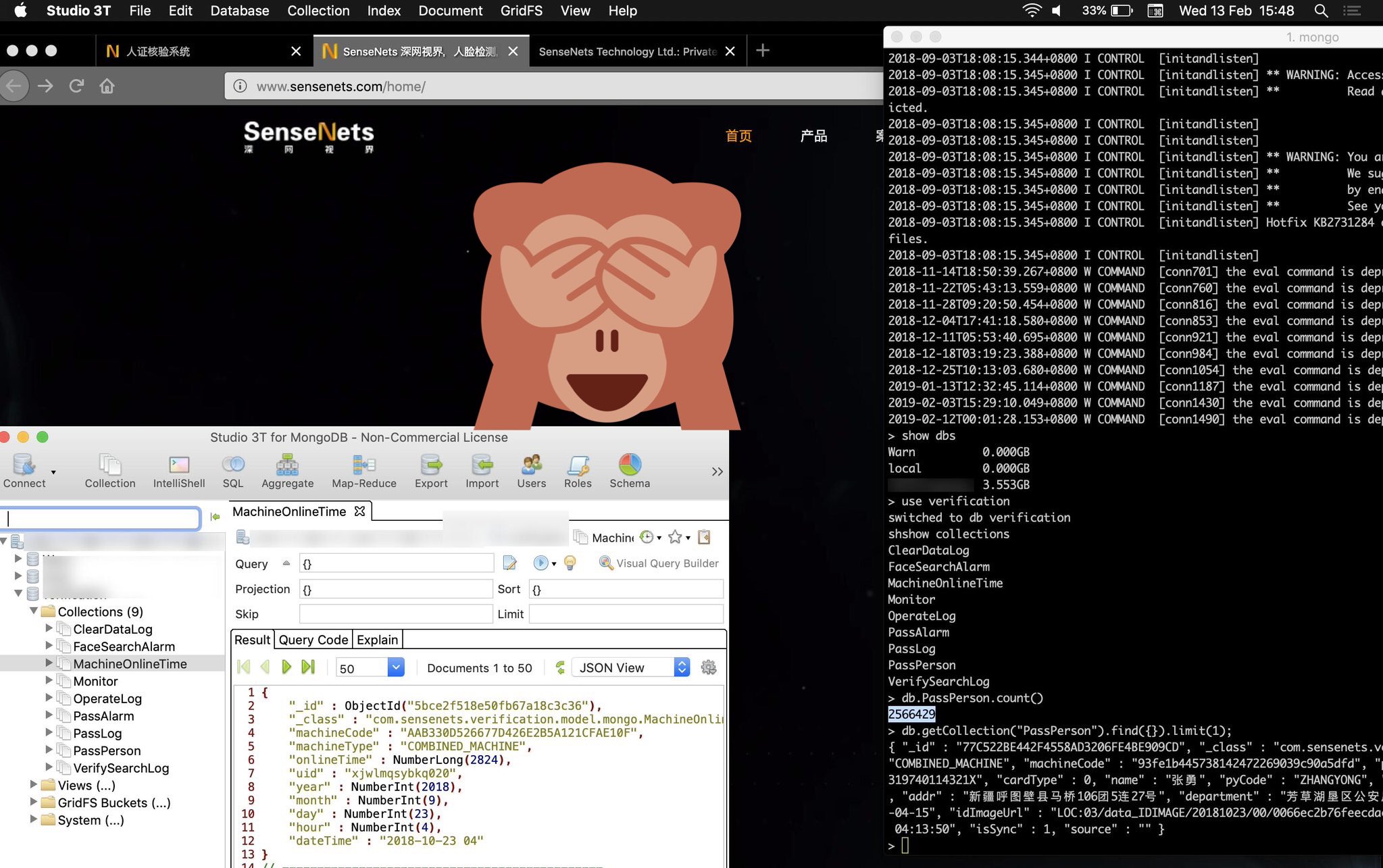

The security lapse was discovered by Victor Gevers at the GDI Foundation, a security organization working in the public’s interest. Using the infamous but useful Shodan search engine, he found a MongoDB instance owned by the Chinese company SenseNets that stored an ever-increasing number of data points from a facial recognition system apparently at least partially operated by the Chinese government.

Many of the targets of this system were Uyghur Muslims, an ethnic and religious minority in China that the country has persecuted in what it considers secrecy, isolating them in remote provinces in what amount to religious gulags.

This database was no limited sting operation: some 2.5 million people had their locations and other data listed in it. Gevers told me that data points included national ID card number with issuance and expiry dates; sex; nationality; home address; DOB; photo; employer; and known previously visited face detection locations.

This data, Gevers said, plainly “had been visited multiple times by visitors all over the globe. And also the database was ransacked somewhere in December by a known actor,” one known as Warn, who has previously ransomed poorly configured MongoDB instances. So it’s all out there now.

A bad idea, poorly executed, with sad parallels

First off, it is bad enough that the government is using facial recognition systems to target minorities and track their movements, especially considering the treatment many of these people have already received. The ethical failure on full display here is colossal, but unfortunately no more than we have come to expect from an increasingly authoritarian China.

Using technology as a tool to track and influence the populace is a proud bullet point on the country’s security agenda, but even allowing for the cultural differences that produce something like the social credit rating system, the wholesale surveillance of a minority group is beyond the pale. (And I say this in full knowledge of our own problematic methods in the U.S.)

But to do this thing so poorly is just embarrassing, and should serve as a warning to anyone who thinks a surveillance state can be well administrated — in Congress, for example. We’ve seen security tech theater from China before, in the ineffectual and likely barely functioning AR displays for scanning nearby faces, but this is different — not a stunt but a major effort and correspondingly large failure.

The duty of monitoring these citizens was obviously at least partially outsourced to SenseNets (note this is different from SenseTime, but many of the same arguments will apply to any major people-tracking tech firm), which in a way mirrors the current controversy in the U.S. regarding Amazon’s Rekognition and its use — though on a far, far smaller scale — by police departments. It is not possible for federal or state actors to spin up and support the tech and infrastructure involved in such a system on short notice; like so many other things, the actual execution falls to contractors.

And as SenseNets shows, these contractors can easily get it wrong, sometimes disastrously so.

MongoDB, it should be said, is not inherently difficult to secure; it’s just a matter of choosing the right settings in deployment (settings that are now but were not always the defaults). But for some reason people tend to forget to check those boxes when using the popular system; over and over we’ve seen poorly configured instances being accessible to the public, exposing hundreds of thousands of accounts. This latest one must surely be the largest and most damaging, however.

Gevers pointed out that the server was also highly vulnerable to MySQL exploits among other things, and was of course globally visible on Shodan. “So this was a disaster waiting to happen,” he said.

In fact it was a disaster waiting to happen twice; the company re-exposed the database a few days after securing it, after I wrote this story but before I published:

Living in a glass house

The truth is, though, that any such centralized database of sensitive information is a disaster waiting to happen, for pretty much everyone involved. A facial recognition database full of carefully organized demographic data and personal movements is a hell of a juicy target, and as the SenseTimes instance shows, malicious actors foreign and domestic will waste no time taking advantage of the slightest slip-up (to say nothing of a monumental failure).

We know major actors in the private sector fail at this stuff all the time and, adding insult to injury, are not held responsible — case in point: Equifax. We know our weapons systems are hackable; our electoral systems are trivial to compromise and under active attack; the census is a security disaster; and unsurprisingly the agencies responsible for making all these rickety systems are themselves both unprepared and ignorant, by the government’s own admission… not to mention unconcerned with due process.

The companies and governments of today are simply not equipped to handle the enormousness, or recognize the enormity, of large-scale surveillance. Not only that, but the people that compose those companies and governments are far from reliable themselves, as we have seen from repeated abuse and half-legal uses of surveillance technologies for decades.

Naturally we must also consider the known limitations of these systems, such as their poor record with people of color, the lack of transparency with which they are generally implemented and the inherently indiscriminate nature of their collection methods. The systems themselves are not ready.

A failure at any point in the process of legalizing, creating, securing, using or administrating these systems can have serious political consequences (such as the exposure of a national agenda, which one can imagine could be held for ransom), commercial consequences (who would trust SenseNets after this? The government must be furious) and, most importantly, personal consequences — to the people whose data is being exposed.

And this is all due (here, in China, and elsewhere) to the desire of a government to demonstrate tech superiority, and of a company to enable that and enrich itself in the process.

In the case of this particular database, Gevers says that although the policy of the GDI is one of responsible disclosure, he immediately regretted his role. “Personally it made angry after I found out that I unknowingly helped the company secure its oppression tool,” he told me. “This was not a happy experience.”

The best we can do, and which Gevers did, is to loudly proclaim how bad the idea is and how poorly it has been done, is being done and will be done.

from TechCrunch https://tcrn.ch/2GzSlGC

No comments

Post a Comment