Tufts expelled a student for grade hacking. She claims innocence

As she sat in the airport with a one-way ticket in her hand, Tiffany Filler wondered how she would pick up the pieces of her life, with tens of thousands of dollars in student debt and nothing to show for it.

A day earlier, she was expelled from Tufts University veterinary school. As a Canadian, her visa was no longer valid and she was told by the school to leave the U.S. “as soon as possible.” That night, her plane departed the U.S. for her native Toronto, leaving any prospect of her becoming a veterinarian behind.

Filler, 24, was accused of an elaborate months-long scheme involving stealing and using university logins to break into the student records system, view answers, and alter her own and other students’ grades.

The case Tufts presented seems compelling, if not entirely believable.

There’s just one problem: In almost every instance that the school accused Filler of hacking, she was elsewhere with proof of her whereabouts or an eyewitness account and without the laptop she’s accused of using. She has alibis: fellow students who testified to her whereabouts; photos with metadata putting her miles away at the time of the alleged hacks; and a sleep tracker that showed she was asleep during others.

Tufts is either right or it expelled an innocent student on shoddy evidence four months before she was set to graduate.

– – –

Guilty until proven innocent

Tiffany Filler always wanted to be a vet.

Ever since she was a teenager, she set her sights on her future career. With almost four years under her belt at Tufts, which is regarded as one of the best schools for veterinary medicine in North America, she could have written her ticket to any practice. Her friends hold her in high regard, telling me that she is honest and hardworking. She kept her head down, earning cumulative grade point averages of 3.9 for her masters and 3.5 for her doctorate.

For a time, she was even featured on the homepage of Tufts’ vet school. She was a model final-year student.

Tufts didn’t see it that way.

Filler was called into a meeting on the main campus on August 22 where the university told her of an investigation. She had “no idea” about the specifics of the hacking allegations, she told me on a phone call, until October 18 when she was pulled out of her shift, still in her bloodied medical scrubs, to face the accusations from the ethics and grievance committee.

For three hours, she faced eight senior academics, including one who is said to be a victim of her alleged hacks. The allegations read like a court docket, but Filler said she went in knowing nothing that she could use to defend herself.

Tufts said she stole a librarian’s password to assign a mysteriously created user account, “Scott Shaw,” with a higher level of system and network access. Filler allegedly used it to look up faculty accounts and reset passwords by swapping out the email address to one she’s accused of controlling, or in some cases obtaining passwords and bypassing the school’s two-factor authentication system by exploiting a loophole that simply didn’t require a second security check, which the school has since fixed.

Tufts accused Filler of using this extensive system access to systematically log in as “Scott Shaw” to obtain answers for tests, taking the tests under her own account, said to be traced from either her computer — based off a unique identifier, known as a MAC address — and the network she allegedly used, either the campus’s wireless network or her off-campus residence. When her grades went up, sometimes other students’ grades went down, the school said.

In other cases, she’s alleged to have broken into the accounts of several assessors in order to alter existing grades or post entirely new ones.

Tiffany Filler, left, with her mother in a 2017 photo at Tufts University.

The bulk of the evidence came from Tufts’ IT department, which said each incident was “well supported” from log files and database records. The evidence pointed to her computer over a period of several months, the department told the committee.

“I thought due process was going to be followed,” said Filler, in a call. “I thought it was innocent until proven guilty until I was told ‘you’re guilty unless you can prove it.'”

Like any private university, Tufts can discipline — even expel — a student for almost any reason.

“Universities can operate like shadow criminal justice systems — without any of the protections or powers of a criminal court,” said Samantha Harris, vice president of policy research at FIRE, a rights group for America’s colleges and universities. “They’re without any of the due process protections for someone accused of something serious, and without any of the powers like subpoenas that you’d need to gather all of the technical evidence.”

Students face an uphill battle in defense of any charges of wrongdoing. As was the case with Filler, many students aren’t given time to prepare for hearings, have no right to an attorney, and are not given any or all of the evidence. Some of the broader charges, such as professional misconduct or ethical violations, are even harder to fight. Grade hacking is one such example — and one of the most serious offenses in academia. Where students have been expelled, many have also faced prosecution and the prospect of serving time in prison on federal computer hacking charges.

Harris reviewed documents we provided outlining the university’s allegations and Filler’s appeal.

“It’s troubling when I read her appeal,” said Harris. “It looks as though [the school has] a lot of information in their sole possession that she might try to use to prove her innocent, and she wasn’t given access to that evidence.”

Access to the university’s evidence, she said, was “critical” to due process protections that students should be given, especially when facing suspension or expulsion.

A month later, the committee served a unanimous vote that Filler was the hacker and recommended her expulsion.

– – –

A RAT in the room

What few facts Filler and Tufts could agree on is that there almost certainly was a hacker. They just disagreed on who the hacker was.

Struggling for answers and convinced her MacBook Air — the source of the alleged hacks — was itself compromised, she paid for someone through freelance marketplace Fiverr to scan her computer. Within minutes, several malicious files were found, chief among which were two remote access trojans — or RATs — commonly used by jilted or jealous lovers to spy on their exes’ webcams and remotely control their computers over the internet. The scan found two: Coldroot and CrossRAT. The former is easily deployed, and the other is highly advanced malware, said to be linked to the Lebanese government.

Evidence of a RAT might suggest someone had remote control of her computer without her knowledge. But existence of both on the same machine, experts say, is unlikely if not entirely implausible.

Thomas Reed, director of Mac and Mobile at Malwarebytes, the same software used to scan Filler’s computer, confirmed the detections but said there was no conclusive evidence to show the malware was functional.

“The Coldroot infection was just the app and was missing the launch daemon that would have been key to keeping it running,” said Reed.

Even if it were functional, how could the hacker have framed her? Could Filler have paid someone to hack her grades? If she paid someone to hack her grades, why implicate her — and potentially the hacker — by using her computer? Filler said she was not cautious about her own cybersecurity — insofar that she pinned her password to a corkboard in her room. Could this have been a stitch-up? Was someone in her house trying to frame her?

The landlord told me a staff resident at Tufts veterinary school, who has since left the house, “has bad feelings” and “anger” toward Filler. The former housemate may have motive but no discernible means. We reached out to the former housemate for comment but did not hear back, and therefore are not naming the person.

Filler took her computer to an Apple Store, claiming the “mouse was acting on its own and the green light for the camera started turning on,” she said. The support staff backed up her files but wiped her computer, along with any evidence of malicious software beyond a handful of screenshots she took as part of the dossier of evidence she submitted in her appeal.

It didn’t convince the grievance committee of possible malicious interference.

“Feedback from [IT] indicated that these issues with her computer were in no way related to the alleged allegations,” said Angie Warner, the committee’s acting chair, in an email we’ve seen, recommending Filler’s expulsion. Citing an unnamed IT staffer, the department claimed with “high degree of certainty” that it was “highly unlikely” that the grade changes were “performed by malicious software or persons without detailed and extensive hacking ability.”

Unable to prove who was behind the remote access malware — or even if it was active — she turned back to fighting her defense.

– – –

‘Why wait?’

It took more than a month before Filler would get the specific times of the alleged hacks, revealing down to the second when each breach happened

Filler thought she could convince the committee that she wasn’t the hacker, but later learned that the timings “did not factor” into the deliberations of the grievance committee, wrote Tufts’ veterinary school dean Joyce Knoll in an email dated December 21.

But Filler said she could in all but a handful of cases provide evidence showing that she was not at her computer.

In one of the first allegations of hacking, Filler was in a packed lecture room, with her laptop open, surrounded by her fellow vet school colleagues both besides and behind her. We spoke to several students who knew Filler — none wanted to be named for fear of retribution from Tufts — who wrote letters to testify in Filler’s defense.

All of the students we spoke to said they were never approached by Tufts to confirm or scrutinize their accounts. Two other classmates who saw Filler’s computer screen during the lecture told me they saw nothing suspicious — only her email or the lecture slides.

Another time Filler is accused of hacking, she was on rounds with other doctors, residents and students to discuss patients in their care. One student said Filler was “with the entire rotation group and the residents, without any access to a computer” for two hours.

For another accusation, Filler was out for dinner in a neighboring town. “She did not have her laptop with her,” said one of the fellow student who was with Filler at dinner. The other students sent letters to Tufts in her defense. Tufts said on that occasion, her computer — eight miles away from the restaurant — was allegedly used to access another staff member’s login and tried to bypass the two-factor authentication, using an iPhone 5S, a model Filler doesn’t own. Filler has an iPhone 6. (We asked an IT systems administrator at another company about Duo audit logs: They said if a device not enrolled with Duo tried to enter a valid username and password but couldn’t get past the two-factor prompt, the administrator would only see the device’s software version and not see the device type. A Duo spokesperson confirmed that the system does not collect device names.)

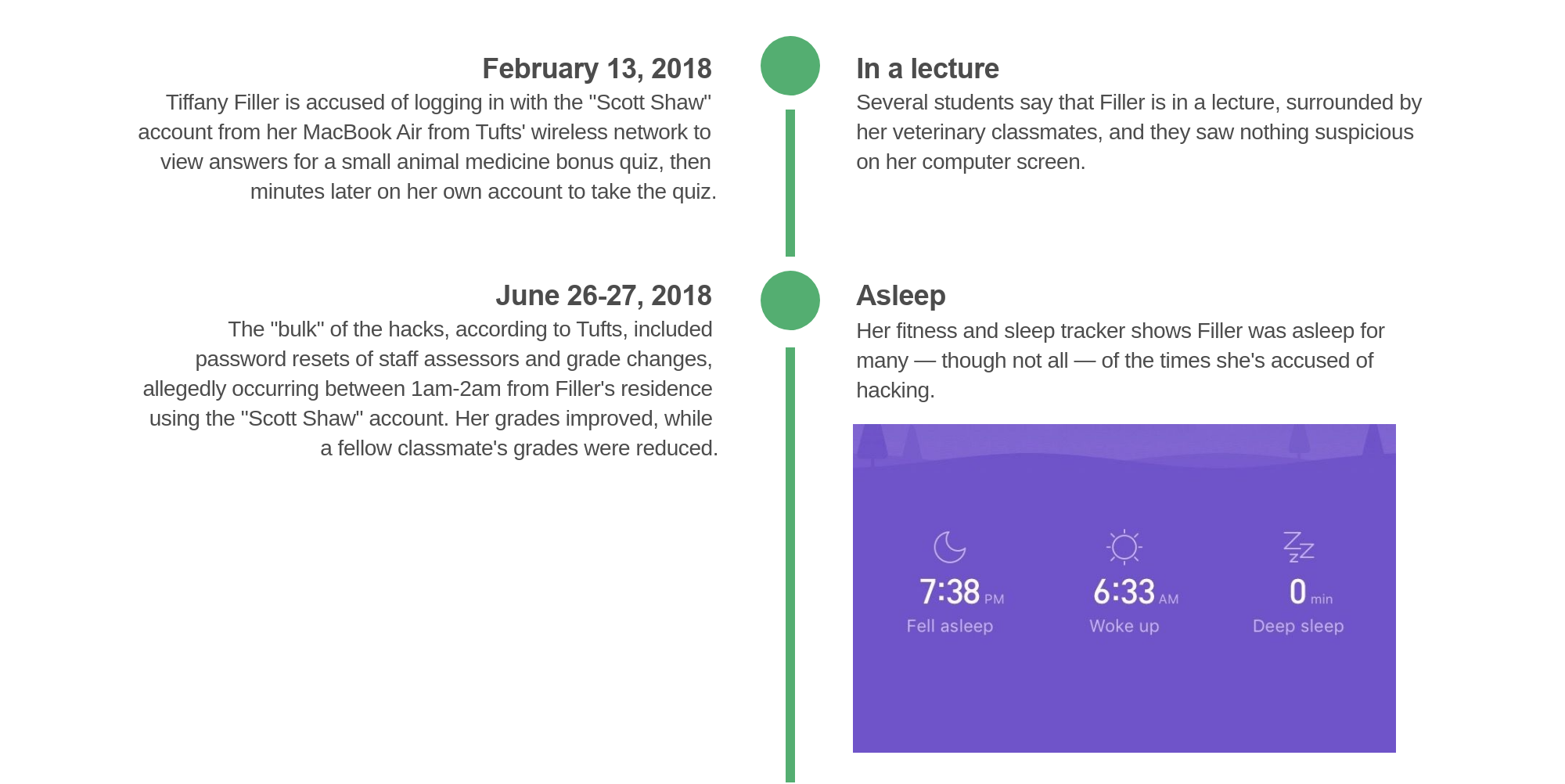

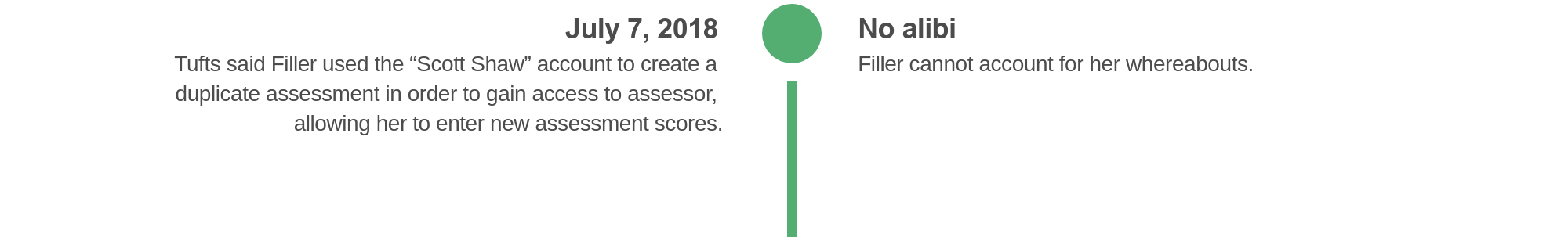

Filler, who wears a Xiaomi fitness and sleep tracker, said the tracker’s records showed she was asleep in most, but not all of the times she’s accused of hacking. She allowed TechCrunch to access the data in her cloud-stored account, which confirmed her accounts.

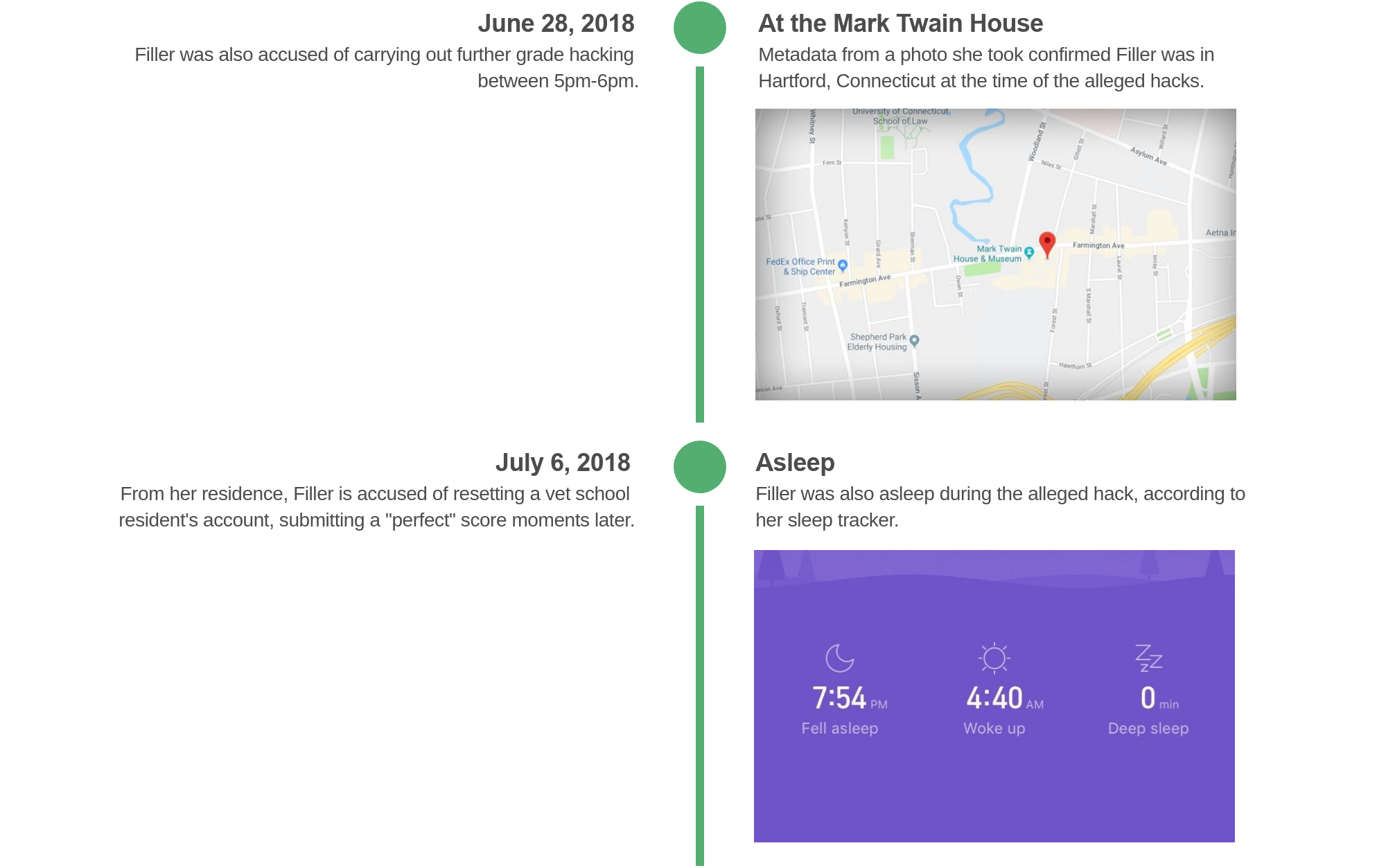

The list of accusations included a flurry of activity from her computer at her residence, Tufts said took place between 1am and 2am on June 27, 2018 — during which her fitness tracker shows she was asleep — and from 5:30 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. on June 28, 2018.

But Filler was 70 miles away visiting the Mark Twain House in neighboring Hartford, Connecticut. She took two photos of her visit — one of her in the house, and another of her standing outside.

We asked Jake Williams, a former NSA hacker who founded cybersecurity and digital forensics firm Rendition Infosec, to examine the metadata embedded in the photos. The photos, taken from her iPhone, contained a matching date and time for the alleged hack, as well as a set of coordinates putting her at the Mark Twain House.

While photo metadata can be modified, Williams said the signs he expected to see for metadata modification weren’t there. “There is no evidence that these were modified,” he said.

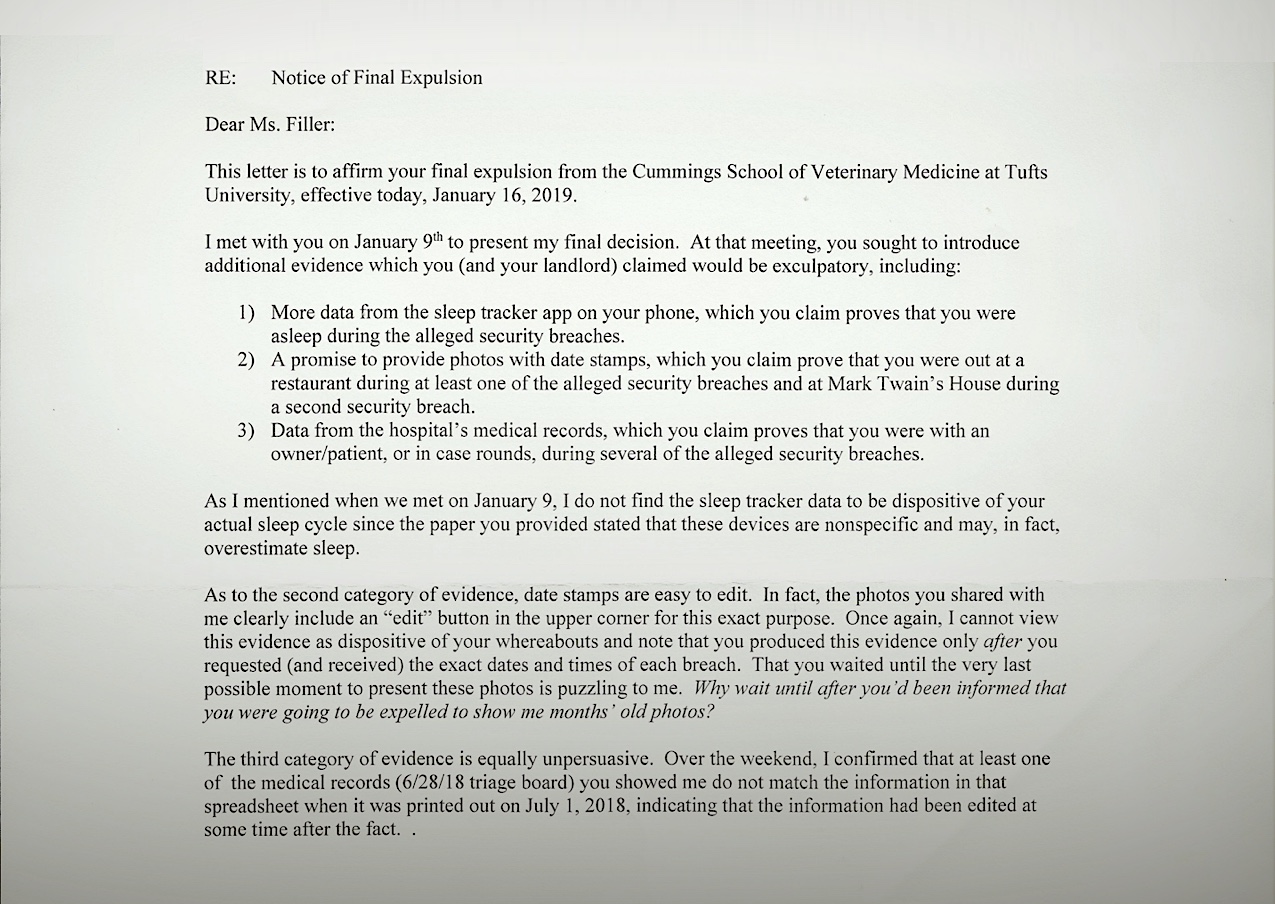

Yet none of it was good enough to keep her enrolled at Tufts. In a letter on January 16 affirming her expulsion, Knoll rejected the evidence.

“Date stamps are easy to edit,” said Knoll. “In fact, the photos you shared with me clearly include an ‘edit’ button in the upper corner for this exact purpose,” she wrote, referring to the iPhone software’s native photo editing feature. “Why wait until after you’d been informed that you were going to be expelled to show me months’ old photos?” she said.

“My decision is final,” said her letter. Filler was expelled.

Filler’s final expulsion letter. (Image: supplied)

– – –

The little things

Filler is back home in Toronto. As her class is preparing to graduate without her in May, Tufts has already emailed her to begin reclaiming her loans.

News of Filler’s expulsion was not unexpected given the drawn-out length of the investigation, but many were stunned by the result, according to the students we spoke to. From the time of the initial investigation, many believed Filler would not escape the trap of “guilty until proven innocent.”

“I do not believe Tiffany received fair treatment,” said one student. “As a private institution, it seems like we have few protections [or] ways of recourse. If they could do this to Tiffany, they could do it to any of us.”

TechCrunch sent Tufts a list of 19 questions prior to publication — including if the university hired qualified forensics specialists to investigate, and if law enforcement was contacted and whether the school plans to press criminal charges for the alleged hacking.

“Due to student privacy concerns, we are not able to discuss disciplinary matters involving any current or former student of Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University,” said Tara Pettinato, a Tufts spokesperson. “We take seriously our responsibility to ensure our students’ privacy, to maintain the highest standards of academic integrity, and to adhere to our policies and processes, which are designed to be fair and equitable to all students.”

We asked if the university would answer our questions if Filler waived her right to privacy. The spokesperson said the school “is obligated to follow federal law and its own standards and practices relating to privacy,” and would not discuss disciplinary matters involving any current or former student.

The spokesperson declined to comment further.

But even the little things don’t add up.

Tufts never said how it obtained her IP address. Her landlord told me Tufts never asked for it, let alone confirmed it was accurate. Courts have thrown out cases that rely on them as evidence when others share the same network. MAC addresses can identify devices but can be easily spoofed. Filler owns an iPhone 6, not an iPhone 5S, as claimed by Tufts. And her computer name was different to what Tufts said.

And how did she allegedly get access to the “Scott Shaw” password in the first place?

Warner, the committee chair, said in a letter that the school “does not know” how the initial librarian’s account was compromised, and that it was “irrelevant” if Filler even created the “Scott Shaw” account.

Many accounts were breached as part of this apparent elaborate scheme to alter grades, but there is no evidence Tufts hired any forensics experts to investigate. Did the IT department investigate with an inherent confirmation bias to try to find evidence that connected Filler’s account with the suspicious activity, or were the allegations constructed after Filler was identified as a suspect? And why did the university take months from the first alleged hack to move to protect user accounts with two-factor authentication, and not sooner?

“The data they are looking at doesn’t support the conclusions they’ve drawn,” said Williams, following his analysis of the case. “It’s entirely possible that the data they’re relying on — is far from normal or necessary burdens of evidence that you would use for an adverse action like this.

“They did DIY forensics,” he continued. “And they opened themselves up to legal exposure by doing the investigation themselves.”

Not every story has a clear ending. This is one of them. As much as you would want answers reading this far into the story, we do, too.

But we know two things for certain. First, Tufts expelled a student months before she was set to graduate based on a broken system of academic-led, non-technical committees forced to rely on weak evidence from IT technicians who had no discernible qualifications in digital forensics. And second, it doesn’t have to say why.

Or as one student said: “We got her side of the story, and Tufts was not transparent.”

Extra Crunch members — join our conference call on Tuesday, March 12 at 11AM PST / 2PM EST with host Zack Whittaker. He’ll discuss the story’s developments and take your questions. Not a member yet? Learn more about Extra Crunch and try it free.

Read more on TechCrunch:

- Two hackers behind 2016 Uber data breach have been indicted for another hack

- Millions of bank loan and mortgage documents have leaked online

- Hackers are spreading Islamic State propaganda by hijacking Twitter accounts

- Many popular iPhone apps secretly record your screen without asking

- Dow Jones’ watchlist of 2.4 million high-risk individuals has leaked

- India’s state gas company leaks millions of Aadhaar numbers

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2C97vic

No comments

Post a Comment